The Reconstruction Era

The Great Whitelash - Part Two

This is part two of the Making America White Again series. Feel free to read part one here. This series aims to look at our current moment in history, not as an aberration, but a continuation of what I’m calling the great whitelash.

Before we get into the horrors perpetrated by white supremacists during the Reconstruction Era, it’s important to note the obvious event that preceded it; The Civil War.

While revisionists today are vague about the primary reason for the Southern states to secede from the Union to form the Confederate States of America, the actual Confederate soldiers were not so obtuse. Their Vice President, Alexander Stephens, was pretty clear on the confederacy’s views. In his infamous “Cornerstone Speech,” he plainly said:

“Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

That’s as clear as it gets. They were so committed to this belief that they waged a Civil War that ended up killing over 750,000 people. While the South was defeated in battle and slavery became illegal in the entire continent, this obviously didn’t stop their beliefs of superiority. It’s also important to note that slavery was big business. It wasn’t just ideological. Enslaved black people represented billions of dollars in human property, thus making slave owners among the wealthiest men in the Western world.

This war was economic and cultural.

The Union’s victory in 1865 destroyed slavery as a legal institution through the Thirteenth Amendment. But it did not destroy the ideology that justified slavery. The Confederates lost the war, but white supremacy won the country.

Enter the Reconstruction Era.

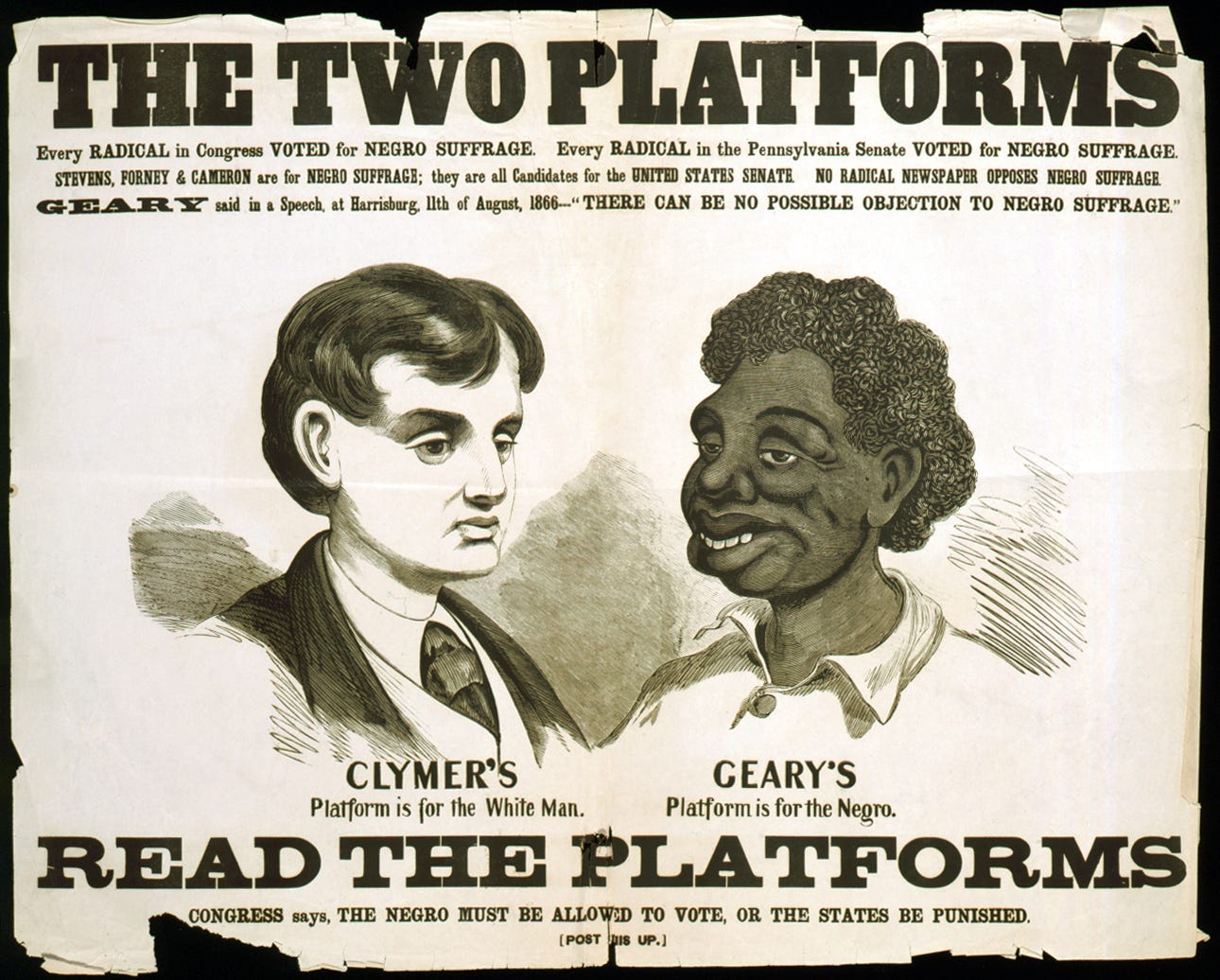

After the Civil War ended, an effort was made to establish a semblance of Democracy. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments were passed, which ended slavery, established citizenship for the newly freed slaves, and guaranteed the right to vote for African American men, respectively.

These were rights guaranteed on paper, but the South had not given up on their lost cause. Less than a year after the official end of the war, all hell broke loose. And it was only the beginning.

In Memphis, in the spring of 1866, there was a small fight between Black Union veterans and white police officers, who were Irish immigrants, and did not see freedmen as fellow workers trying to survive, but as competition that needed to be put back in its place.

That small scuffle is all it took for the white rage to take over. For three days, the city descended into violence.

The police were not bystanders. They were active participants. Black neighborhoods were invaded deliberately, one street at a time. Homes were looted. People were beaten, shot, left where they fell. The schools went up first; new buildings, barely standing, symbols of something dangerous: Black education, Black ambition, Black futures. Churches followed soon after. Any space where black people gathered to imagine a life beyond survival had to be destroyed.

When it was over, forty-six black men, women, and children were dead. Dozens more were injured. Black women were raped, not as random acts of lawlessness, but as a message: This is what happens when you forget your place.

Two months later, New Orleans was the setting of the next massacre.

Black citizens and white Republicans gathered to support a constitutional convention. Nothing radical by today’s standards. Just the possibility of universal male suffrage. The suggestion that Black men might vote or hold office was provocation enough.

Police and former Confederates answered it with gunfire.

What unfolded inside the Mechanics Institute was not a riot. It was an execution. Men who tried to surrender were shot anyway. Others were hunted through the building, then killed. Bodies piled where debate was supposed to happen. General Philip Sheridan did not soften the language. He called it what it was: a massacre.

The message was unmistakable, and it traveled quickly: Reconstruction would exist on paper.

However, Congress briefly acted on behalf of its black citizens.

Federal troops arrived, and with them came new laws. The Fourteenth Amendment. The Reconstruction Acts. For a brief moment, the system worked as advertised. Black men voted. Black men held office. Statehouses across the South began to change, not just in composition but in meaning. And the South responded the only way it knew how. The Ku Klux Klan emerged alongside the Knights of the White Camelia. Rifle clubs followed, respectable on the surface, but lethal in practice. This was not spontaneous violence or regional instability. It was strategy. Remove the leaders. Terrify the voters. Shatter the alliances that made multiracial democracy possible.

In St. Landry Parish, that strategy unfolded in plain sight. White vigilantes hunted black families for weeks, driving them through fields and swamps, dragging them from homes that offered no protection. By the time it ended, at least two hundred people were dead, likely more. When the ballots were finally counted, the Republican vote totaled zero.

By 1873, the federal government was worn down. The appetite for enforcement was gone. The country wanted closure. White supremacists understood what that meant.

In Colfax, Louisiana, they gathered openly, armed with rifles and a cannon. Black Republicans took up positions inside the courthouse, still believing the law might hold if they held long enough. It was Easter Sunday. Smoke filled the air. Then fire.

When the building burned, men fled with their hands raised, trusting surrender to mean survival.

It did not.

Some were shot as they ran. Others were taken prisoner, lined up, and executed after the fighting stopped. Their bodies were left behind as a warning. The death toll was never settled. Sixty. A hundred. Perhaps more. The exact number mattered less than the lesson. The state would not protect them, and the courts would make certain it never had to.

When the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government lacked the authority to prosecute the men responsible, it did more than interpret the law. It removed the last barrier. Private terror was now officially beyond federal reach.

After that, there was no reason to hide.

The Mississippi Plan formalized what had already been happening on the ground. Violence and intimidation were no longer improvised. They were organized. Armed men appeared at polling places, not to vote, but to watch who did. Landlords and employers took over where guns did not, making it clear that a job, a home, or a line of credit depended on political obedience. Rifle clubs drilled openly in towns and cities, signaling that enforcement would be public and unquestioned.

The consequences followed quickly. In Vicksburg, a duly elected Black sheriff was pushed out of office by force. In Clinton, a political rally drew a crowd and ended in a manhunt, with participants chased down long after speeches were supposed to be over. People were killed in the process, and others learned the lesson without needing to see the bodies themselves. When the votes were finally tallied, the results bore little resemblance to the will of the electorate.

Democracy, it turned out, did not have to be debated. It could be beaten into submission.

South Carolina followed the same path. Red Shirts replaced white hoods. Intimidation moved into the open. Surrenders were accepted and then ignored. Entire counties were emptied of political opposition through fear alone.

By 1877, Reconstruction was finished. Not because it failed, but because it was deliberately destroyed. And the country, exhausted and complicit, chose not to hold anyone accountable. Southern Democrats agreed to accept Rutherford B. Hayes as president, only if he agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South. With the soldiers gone, and federal authority retreated, white supremacy filled the void. The Compromise of 1877, as it is now called, was an abandonment.

That choice did not stay in the past. It echoes until today. What came next were the Jim Crow laws that segregated and disenfranchised African Americans for nearly a hundred years.

These were not the only massacres, beatings, or lynchings. In fact, the KKK was only getting started. But these events I recounted should suffice as evidence of the immediate whitelash at the very thought or possibility of black advancement. Although most of the victims were African American, it’s important to also mention that nearly 600 Mexicans were lynched during this time period and up to the 1920s. Anyone who wasn’t a white man was in danger of losing their life.

White supremacy is an insidious belief. It morphs and finds ways to keep spreading itself. Whenever marginalized groups have made strides toward advancements, the people who believe themselves to be white have pushed back through violence, unfair laws, and other devious machinations. Today, we see it most clearly in the form of ICE and in the cadre of racist measures and executive actions enacted by this administration.

In the next essay, I will focus on the Jim Crow laws and how that eventually led to the Civil Rights movement.

I may also have smaller deviations, whether a historical footnote, or examining someone’s life. I hope you follow me along for those, too.

And speaking of following, I decided to create a TikTok account. The impetus was to start talking about books on how to resist this regime and ways to organize. So, follow me on there? Click here to get to my profile.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

This work requires reading from many primary sources, as well as distillation into a compelling and comprehensive narrative. Please, if you’re able to do so, consider upgrading your subscription.

Thanks for reading.

Further Reading

Making America White Again (Part One)

The Red Record by Ida B. Wells

Powerful work documenting the institutional mechanisms behind Reconstruction violence. The detial about how the Mississippi Plan formalized intimidation really underscores how terror became policy rather than anomaly. I hadn't fully considered how the 1877 compromise essentially handed the infrastructure of suppression back with federal blessing, setting up decades of entrenched systems.